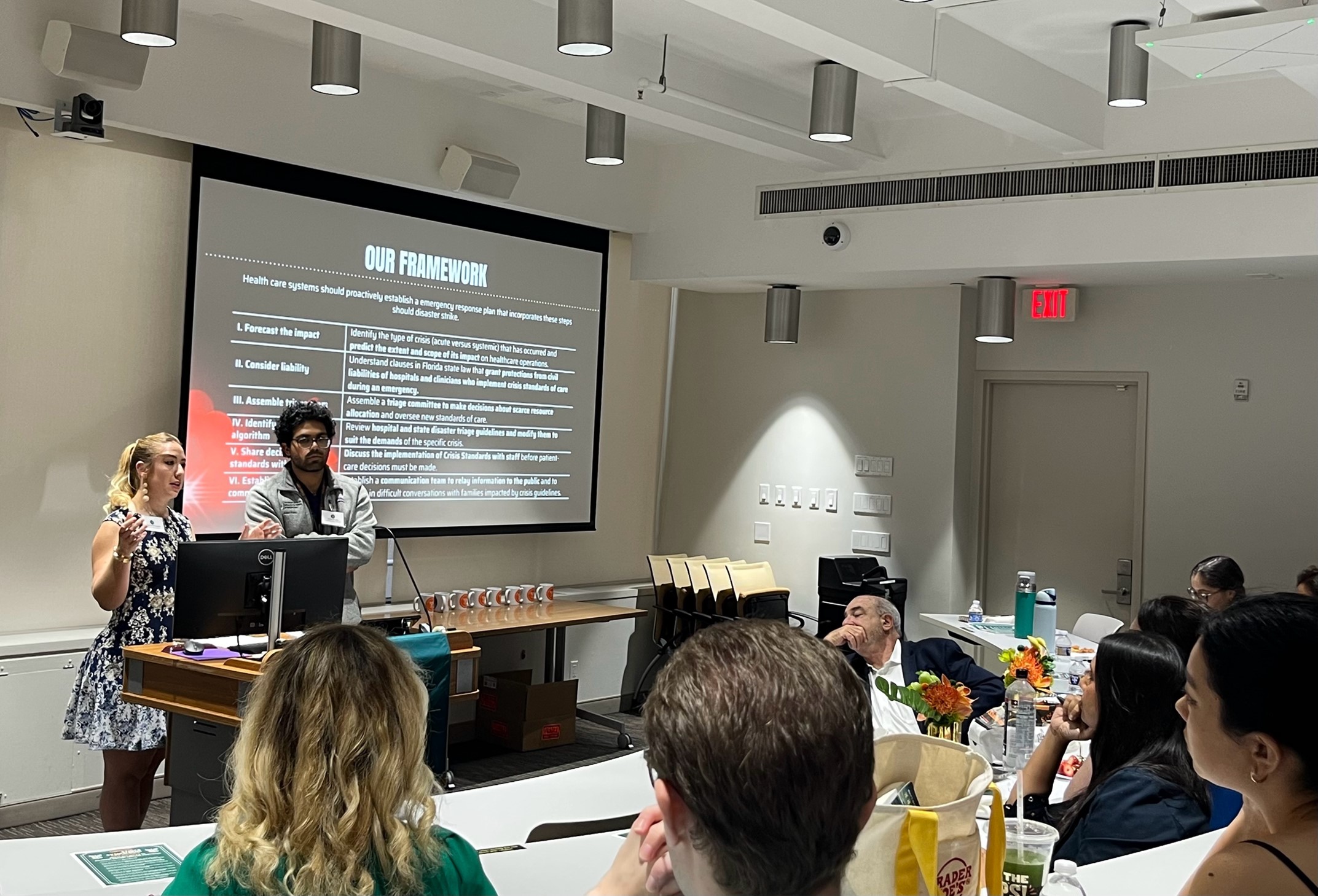

Public health emergencies pose extraordinary if not unprecedented challenges for health care systems, institutions, and practitioners. Many of these challenges are shaped by shortages of people, equipment, medication and/or appropriate treatment venues. When systems, institutions, or clinicians lack adequate resources, it is both unrealistic and inappropriate to expect or require them to conduct operations according to non-emergency standards. For this reason, many states have adopted “crisis standards of care” policies, guidelines, and laws to govern such altered standards. During the Covid-19 pandemic, critical decisions about scarce resources were happening in real time with less centralized guidance than would be expected for decisions of this magnitude. Therefore, we set out to create overarching ethically optimized, evidence-based guidelines on how systems and leaders should make critical decisions about scarce resources when disasters strike. These guidelines are intended to be widely applicable to many types of disasters: hurricanes, floods, bioterrorism, pandemics, etc, and are intended to be incorporated by the Florida Bioethics Network. They are detailed as follows:

I. Identify the type of crisis (acute versus systemic) that has occurred and predict the extent and scope of its impact on healthcare operations.

II. Understand clauses in Florida state law that grant protections from civil liabilities of hospitals and clinicians who implement crisis standards of care during an emergency.

III. Assemble a triage committee to make decisions about scarce resource allocation and oversee new standards of care.

IV. Review hospital and state disaster triage guidelines and modify them to suit the demands of the specific crisis.

V. Discuss the implementation of Crisis Standards with staff before patient-care decisions must be made.

VI. Establish a communication team to relay information to the public and to engage in difficult conversations with families impacted by crisis guidelines.

By grounding crisis standards in ethical clarity, legal protection, institutional coordination, and compassionate communication, this framework aspires to guide clinical decisions under duress while preserving trust, dignity, and justice.

Redefining Death: The Ethical Debate Surrounding Normothermic Regional Perfusion

Authors: Giselle De La Rua, MS3 & Rachna Rahul, MS3

Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) has emerged as a promising technique to improve the viability and outcomes of organ transplantation following donation after circulatory determination of death (DCDD). In particular, thoracoabdominal NRP (TA-NRP) aims to preserve both thoracic and abdominal organs by restoring in situ perfusion, offering significant potential to expand the donor pool and improve recipient outcomes. However, the adoption of NRP, especially TA-NRP, has ignited ethical debate, centering on its compatibility with established standards for determining death and adherence to the dead donor rule (DDR).

One major ethical concern is that by reestablishing circulation after the declaration of death, TA-NRP may theoretically reverse death determination, particularly if cerebral perfusion is not fully prevented. Though current protocols involve occlusion of the aortic arch vessels to mitigate this risk, critics highlight that collateral circulation could allow some residual brain blood flow. Furthermore, protocols often do not verify the complete absence of brain perfusion, fueling ongoing ethical unease. These concerns are amplified by the principle of nonmaleficence, as invasive interventions during TA-NRP could be perceived as causing harm to donors.

Proponents argue that NRP is initiated only after death is legally declared, with no attempt at donor resuscitation or restoration of spontaneous circulation. They emphasize that mechanical regional perfusion without restoration of independent cardiac function upholds the legal definition of death. Supporters further argue that substantial ischemic injury occurring prior to NRP likely ensures irreversible brain death and point to a limited study by Royo-Villanova et al which found no evidence of perfusion after clamping major vessels. Moreover, they highlight that NRP may reduce organ discard rates, thereby respecting donor autonomy.

The broader ethical debate also touches upon the importance of transparent communication and securing explicit, informed consent. Families must be made fully aware of the specifics of NRP procedures, the goal of resuming limited heart function, and the theoretical risks regarding brain perfusion. Stakeholder trust is crucial as any perception that practices might circumvent ethical boundaries risks undermining public confidence in organ donation. Consequently, many ethicists advocate for cautious implementation of TA-NRP, emphasizing the need for stringent safeguards, empirical validation, and continuous ethical scrutiny.

In conclusion, while NRP offers considerable clinical opportunities, their ethical acceptability remains contested. Ongoing interdisciplinary dialogue, empirical research, and robust procedural safeguards are essential to ensuring these innovations honor donor dignity, respect autonomy, minimize harm, and sustain public trust.

Smart But Soulless? AI’s Ethical Blind Spots in Medical Decision-Making

Author: Soumil Prasad, MS3

Background: Large language models (LLMs) are rapidly entering medical education and clinical workflows, yet early reports suggest that strong factual performance may not translate into reliable ethical reasoning. We compared two state of the art GPT 4–generation models—GPT 4o (multimodal, reinforcement learning from human feedback tuned) and O1 (a GPT 4 class model augmented with retrieval and a rule based safety head)—to quantify this discrepancy.

Methods: Seventy nine multiple choice questions were randomly drawn from AMBOSS, a peer reviewed question bank mapped to the USMLE Step 2 CK blueprint and widely trusted by medical students. The set was balanced between medical ethics items (n = 40) and clinical knowledge items (n = 39). Each model answered each question once under default settings. Accuracy proportions were compared using two proportion Z tests, and a random effects linear probability model with 1,000 bootstrap resamples adjusted for item level variance.

Results: O1 answered 95.0 % of clinical knowledge questions correctly, whereas GPT 4o achieved 75.0 % accuracy (p = 0.012). For medical ethics questions, O1 attained 79.5 % accuracy, while GPT 4o reached 59.0 % (p = 0.050). Within each model, accuracy was significantly higher for clinical than for ethical items, resulting in domain gaps of 15.5 percentage points for O1 and 16.0 percentage points for GPT 4o. The random effects model confirmed that, after adjusting for item difficulty, O1 outperformed GPT 4o by 24.1 percentage points overall (95 % CI 17.8–30.4), and that accuracy for ethics questions was 17.1 percentage points lower than for clinical questions irrespective of model (95 % CI 3.9–30.3). Representative failures included GPT 4o’s recommendation to override a competent minor’s refusal of blood transfusion, whereas O1 respected the refusal but could not cite relevant legal precedent.

Conclusion: Retrieval augmentation and rule based safety policies improve overall accuracy but do not eliminate the ethics deficit in contemporary LLMs. Ethically robust AI will require dedicated training corpora, refined reward functions, and ongoing human oversight. Until such advances occur, clinicians should treat LLM outputs as decision aids rather than moral authorities.

Infectious Influencers: Ethics of Social Media as a Novel Pathogenic Vector

Author: Chase DeLong, MS3

** Winner – Honorable Mention **

The development of human society has led to dense cities, exponential technological advancements, and accessible global travel. Concurrently, the evolution of humankind has been paralleled by that of communicable diseases. Through trade routes, diseases that once threatened individual villages became country-wide epidemics, and urban air travel enabled the rapid dissemination of disease across the world in a span of hours. The most recent demonstration was the COVID-19 pandemic; however, this period also highlighted a new pathogenic vector: social media.

While studies demonstrating a correlation between internet use and depression have been accepted for years, this new contagion has raised more questions than answers, manifesting with physical neurological symptoms. Self-portrayals of motor and vocal tics comparable to Tourette's syndrome surged during the pandemic, initially interpreted as an internet trend. Retrospective evaluation has since revealed a six-fold increase in teen presentations to physicians for such symptoms, ultimately necessitating a new diagnosis altogether: functional tic-like disorder (FTLD). Since the classification of FTLD, further distinctions of "Munchausen's by internet" and "mass social media-induced illness" have been introduced to describe these novel phenomena that do not fit current diagnostic criteria.

While social media has given rise to new diagnoses, existing mental health disorders such as ADHD and autism have become increasingly ambiguous. In the pursuit of maximizing relatability, content creators often oversimplify clinical symptoms and dilute the severity of conditions like ADHD to near-universal human experiences. Medical misinformation is not a new concept, but the rise and spread of new illnesses intertwined with the delegitimization of already stigmatized conditions raises the debate of internet regulation.

In recent years, there have been increasing efforts to protect children online. Florida introduced age requirements for social media accounts and mandates the use of verified state ID to access sites deemed unsafe for minors. This implementation has been fraught with conflict, with many arguing such requirements are an invasion of privacy. As the debate over the best course of action continues, we face the ethical dilemma of freedom versus responsibility. Entrusting the government or tech companies to introduce regulations surrenders the freedom of content access for government-backed online child safety. Accepting responsibility as a parent, pediatrician, teacher, or any individual with the opportunity to facilitate a safe online experience allows for online freedom without government blockades, but carries the risk of exposing children to potentially harmful content.

The Art of Saying “I’m Sorry”: Apology as Accountability in Medicine

Author: Alex Pedowitz, MS3

Apologizing for medical errors is often framed as a communication skill, a mitigation strategy for legal risks, or a form of institutional policy. However, in practice, apologies live in the tension between ethical responsibility, emotional honesty, and uncertainty. They arise not in clear-cut situations, but in morally gray moments—where no single person is to blame, yet someone must still carry the burden of what went wrong.

This work explores apology not as a script, but as a form of ethical presence. In high-stakes, fragmented clinical environments (e.g., emergency medicine, surgery, obstetrics, primary care), errors often unfold across teams and timelines. Providers are frequently left to navigate the aftermath of harm or mishaps they did not directly cause. Whether it is a missed finding, poor communication, or a systems failure, the responsibility to communicate with patients and families often falls unevenly.

Although the ethical obligation to disclose medical errors is well established, the nuanced experience of trainees navigating these scenarios warrants further discussion. The area surrounding trainee moral responsibility—despite proximity to harm—is a critical yet underexplored dimension of modern medical ethics. While trainees may lack formal authority to speak on behalf of the team, patients often perceive them as representatives of the system. Presence and perception, in turn, become their own forms of responsibility, regardless of comfort or level of experience.

To clarify, this tension is not exclusive to learners. Across all roles and specialties, clinicians face the dilemma of how to show up when the truth is blurry, the outcome is irreversible, and words alone feel inadequate.

Therefore, this work proposes a minimalist, human-centered approach to apology: acknowledge the moment, be honest about uncertainty, and remain present without casting blame. Through this framework, apology is reimagined as a relational act—less about admitting fault, and more about honoring experience with care and humility. In doing so, it invites all healthcare workers—not just those “in charge” —to employ apology as one of medicine’s (and humanity’s) strongest tools for building trust and accountability. In moments without a perfect script or a clear way forward, the most ethical and universal tool we have may be the simplest: fill the silence.

Venting in the call room: Burn-out prevention versus the impact on patient care

Author: Danielle Harris, MS3

How do we relieve burdens associated with frustrating patient encounters, without allowing it to plant seeds of implicit biases and generalization, or long-term compromise of patient care? All physicians take the same oath to treat and do no harm. However, while perhaps taboo to say out loud, it is no secret that certain patients make carrying that oath easy, and others can make that commitment laborious. So many factors strain the physician’s view on a doctor-patient relationship, such as antagonistic personalities, zealous family members, limitations within paternalism, etc. So, when faced with a “difficult” patient, we go back to the call team, slump at our desk in the safe enclave of co-med students and co-residents, and vent. Venting about problems, especially to people who understand, is essential. While friends and loved ones in nonhealthcare fields might not understand, our colleagues understand perfectly. Talking about frustrations to an empathetic audience acts as an emotional release and can be therapeutic.

However, medical students often hear opinions from a superior provider that begin to teeter beyond an expression of discontent and into a realm of prejudicial language. This has potential to begin as ignoring symptoms or making assumptions, before snowballing into poor patient outcomes. While some may know to take certain comments said behind closed doors with a grain of salt, it is important to recognize that inappropriate language said in front of trainees can set a poor standard for students who are discovering the kind of doctor they want to be.

It is important to recognize that a safe space amongst colleagues is also necessary. There are risks of telling someone when they have crossed a line, potentially isolating a team member who is overwhelmed and in need of relief and a safe space. Nonetheless, coping mechanisms should not come at the expense of the patient and the level of care they receive. Navigating the subjectivity of what can be “too far” without ruining the sacredness of venting in the call room makes for a rich discussion because it is something that should be established early in medical training while also remaining relevant throughout one’s entire career. As burnout receives more recognition in medical work culture, it is crucial to consider how we integrate various methods in our lives to succeed in stress relief without harming the patient.

Driving Blind: Should Physicians Report Patients with Significant Vision Loss?

Author: David Borden, MS1

Imagine caring for Mrs. Wilson, your 75-year-old patient with advanced glaucoma. Visual field tests show her peripheral vision is dangerously compromised, but she insists her vision is fine. She notes that driving allows her to see her grandkids, go to church, and attend medical appointments. Despite your counseling, she refuses to stop driving, assuring you that she is careful and has never had an accident. What do you do? Do you report her to the Department of Motor Vehicles, potentially violating her trust and jeopardizing her independence, or respect her autonomy and remain silent, knowing she may be putting herself and others at risk?

The decision to report a patient with significant vision loss highlights a complex ethical and legal challenge. In glaucoma and other progressive visual disorders, patients may be unaware of the severity of their impairment, especially when central acuity remains intact. Physicians must weigh their duties to the individual patient against obligations to public safety, often without clear guidance on when the risk justifies breaching confidentiality. This gray area is further complicated by the lack of consensus on what constitutes "fitness to drive," both medically and legally.

State laws and guidelines vary widely. Only a few states mandate physician reporting of medically impaired drivers, while most permit reporting but do not require it. Many DMV websites lack clear instructions, and some states do not shield physicians from liability if sued on the grounds of breaching confidentiality. This legal ambiguity, combined with concerns about damaging patient trust or diminishing quality of life, can lead to inconsistent practice or avoidance of the issue. Many physicians feel unprepared to make driving-related decisions without training, guidelines, or clear clinical criteria.

Ethical considerations of public safety and preventing avoidable harm must be balanced with respect to autonomy and confidentiality. Reporting a patient like Mrs. Wilson might reduce risk to the community, but it may also worsen her isolation, limit her independence, and erode patient trust in the medical system. In areas that lack public transportation, patients may even avoid medical visits for fear of losing their license.

To navigate these challenges, physicians need clearer reporting frameworks, legal protections for good-faith reporting, and interdisciplinary support. Glaucoma, as a condition with imperceptible yet progressive impairment, offers a powerful lens through which to examine how we ethically manage medical fitness to drive.

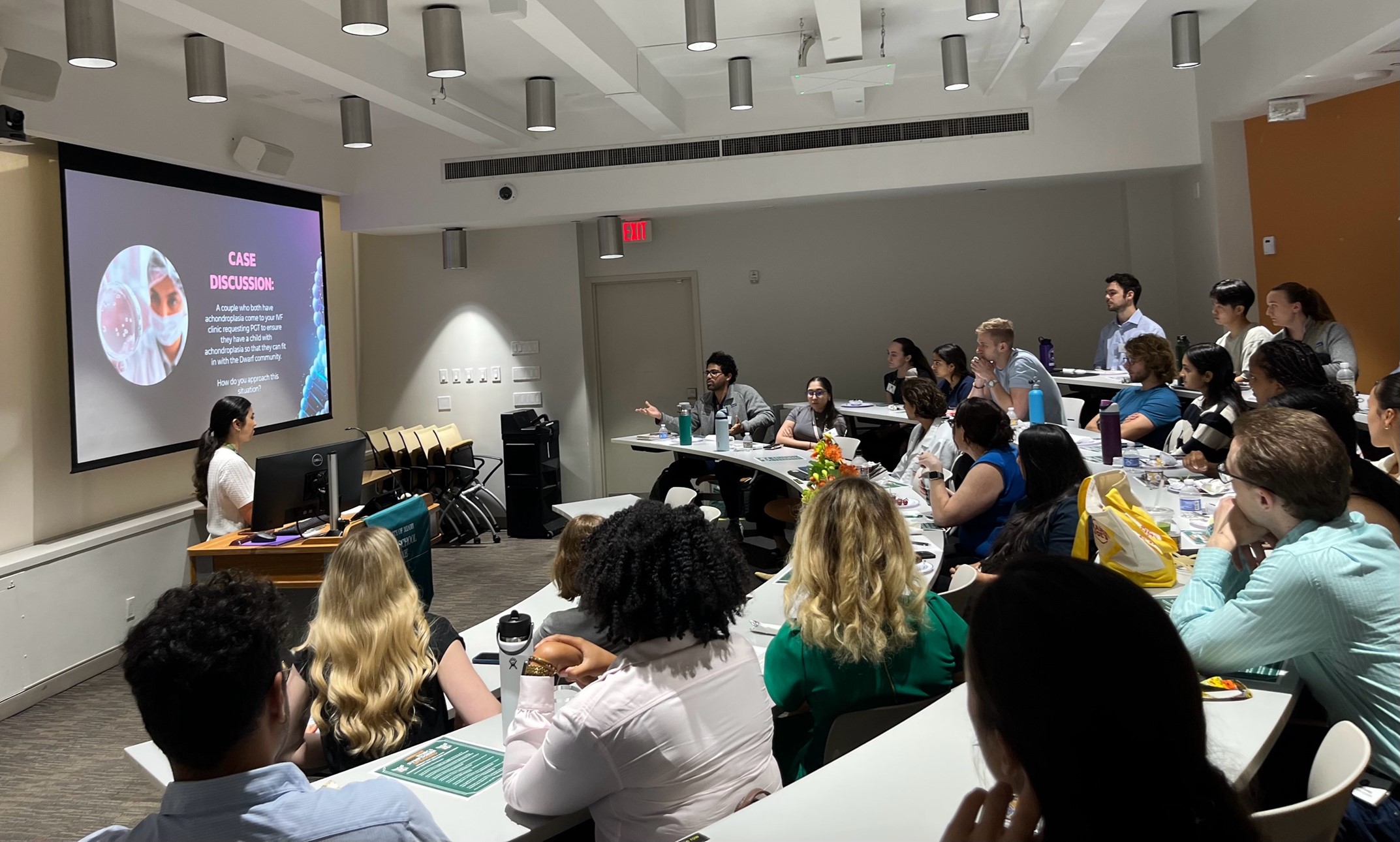

To Design or Not To Design (Babies): Ethics of Pre-implantation Genetic Testing

Author: Isha Harshe, MS2

** Winner – Best Presentation **

Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) involves the analysis of embryonic DNA at the blastocyst stage to detect specific genetic abnormalities, including aneuploidy (PGT-A), monogenic or single-gene disorders (PGT-M), and chromosomal structural rearrangements (PGT-CS), typically performed in the context of in vitro fertilization (IVF). This technology enables the selection of embryos for implantation based on genetic findings, thereby improving IVF success rates, offering individuals with heritable disorders the opportunity to have unaffected offspring, and reducing the need for invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling.

Despite its clinical utility, PGT presents profound ethical challenges. Central questions concern the appropriate scope of testing—specifically, distinguishing between medically indicated uses and non-medical preferences, such as sex selection—and the inherent uncertainties in predicting disease penetrance and expressivity. Furthermore, while PGT may be used to avoid specific high-risk conditions, it cannot guarantee the absence of other genetic mutations that may result in different disorders. Determining which conditions to screen for, particularly those associated with adult-onset diseases or conditions with highly variable phenotypic expression, such as Trisomy 21, further complicates ethical decision-making based on perceived quality of life.

The broader societal implications of widespread genetic screening must also be considered, including potential impacts on societal norms surrounding normalcy, the erosion of genetic diversity, and the marginalization of cultural identities that value traits traditionally regarded as disabilities. Legal developments regarding the status of embryos have introduced additional complexities, raising questions about the ethical permissibility of discarding or indefinitely storing embryos not selected for implantation. Emerging research into the outcomes of implanting genetically “abnormal” embryos challenges the principle of non-maleficence, particularly given the potential for pregnancy complications or spontaneous loss.

While PGT has significantly advanced reproductive medicine and genetics, its increasing role in reproductive decision-making continues to provoke enduring and evolving ethical debates within the medical community.